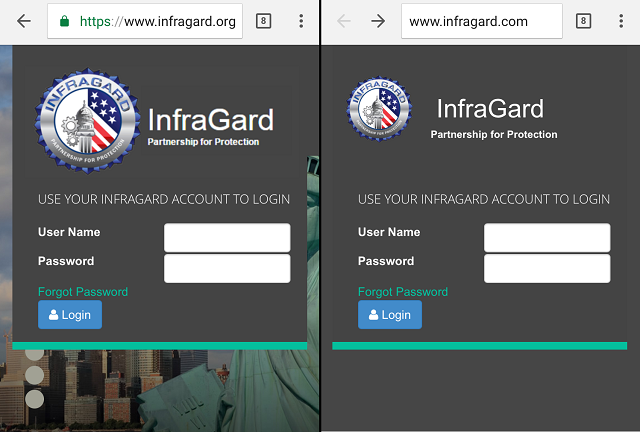

Can you tell which is the real InfraGard login screen?

InfraGard is a partnership between the FBI and private business, created to share information about threats. It consists of members from private business, state and local government agencies, state and local law enforcement agencies, schools and universities. Some of the information shared to members - while not classified - is also not entirely public.

The true web portal for InfraGard is www.infragard.org -- the image on the left.

Someone created a pretty convincing replica of the real portal, at www.infragard.com -- the image on the right. Other than a few outdated images, the only noticeable differences are that the replica domain name ends in .com instead of .org, and the replica is served over non-secure http instead of https.

Thanks to a new feature in Chrome (a feature not yet publicly announced, but one that you can enable with a little tinkering -- scroll to the bottom for a quick how-to), the fake login screen also shows a warning right beneath the password box, telling me I am about to enter my password in an insecure website:

Strangely, as of the time of this writing the impostor doesn't appear to be malicious in nature. The fake login form does in fact send any information submitted to the real InfraGard website, and equally important, to nowhere else (at least in my analysis).

It may be a member trying to be helpful, setting up a .com website to prevent someone with less noble intentions from doing the same. But if that were the case, why the bogus information on the domain registration?

Then again is certainly possible that this is a targeted scam, and that malicious behavior only appears under specific circumstances. A reader suggested this could also be part of a "long con," submitting to the real website for some time and then one day switching to collect passwords.

Long con indeed: the domain registration shows that the domain was created in 2002, and identifies as its registrant an individual at a non-existent address in Tennessee, and a company that dissolved in 2003. The domain registration record was last updated March 6 of this year, for what that is worth.

According to a letter sent to InfraGard members, the FBI is aware of and is investigating the fake website. Regardless, there are a few lessons to be learned.

As a business or hobbyist

Spend a few extra bucks to register website domains similar to your actual one, particularly domains that a customer or employee might go looking for. For instance, of your real website is .net or .org, it is reasonable to think customers that don't know that may instead go looking for .com, and unintentionally stumble into a squatter.

Of course, how far to take that is a judgment call. There is literally no end to the likely typos and visually similar domains an attacker could potentially make use of - but somewhere between nothing and full-on paranoia is the right balance for your business. Put a little thought into it and decide where that balance is for you.

As a consumer

Treat any link sent to you by email, SMS/text message, or social media as suspicious.

Don't log into any website that does not have HTTPS in the address. Any reputable website developer knows to secure the login page. At this point, not doing so is incompetent and grossly negligent - as petroleum newspaper Oil and Gas International discovered (the hard way) last week.

Where possible, enable two-factor authentication (sometimes called login-verification or two-step login) for anything you care about. With this feature, logging in from any new device requires both your password, and your phone (or a code generator, or a U2F key - in other words, the attacker has to both know your password and steal or gain access to something you physically possess).

I am a big fan of password managers, and in particular, website-aware password managers. With this feature, the password manager will give you only the password for the website you are actually on - meaning that if I am on impostor-Facebook.com, the password manager will give me the password for impostor-Facebook (or more likely, nothing at all) and not give up the password to the real Facebook.

Chrome insecure login warnings

Chrome 57 introduced a new feature that makes it obvious when you are logging into an insecure and dangerous website, by displaying a warning right at the password field.

This feature is not yet in the settings menu (and as a test feature, there is no guarantee it will become permanent, though I'd wager chances are very good it will), but you can enable it with a little tinkering.

In the address bar, enter chrome://flags to access a list of optional and loosely documented features. Search for #enable-http-form-warning, and set it to "Enabled."

With this setting enabled, insecure websites will show a warning right under the password field: